Honourable Mavis Kuukua Bissue, Member of Parliament for Ahanta West, has taken a crucial step toward fulfilling her campaign promise to ensure the Ahanta language is taught in schools. On 15th April 2025, she and her team engaged the leadership and academic staff of the Department of Linguistics at the University of Education, Winneba (UEW), to discuss the creation of a curriculum, the training of teachers, and the development of policy guidelines to support the initiative. Here is why her call for the Ahanta language to be taught in schools must be considered.

Ahanta, also known as “Aɣɩnda,” is a dialect of the Akan language family, which is spoken by people in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and other West African countries (Gordon, Jr., 2005). Ahanta is primarily spoken in the Western Region of Ghana, along the coast between the cities of Axim and Sekondi-Takoradi, and it is considered by Obeng (2021) as having relatively minority indigenes and minority users. According to the Ghana Statistical Service (2021) report on the 2021 Population and Housing Census (PHC), the population of the Ahantas, taking into consideration the major districts of Ahanta West, Effia-Kwesimintsim, Sekondi-Takoradi, and Shama Districts, is 689,721.

For many years, the Ahanta language has mainly been used in homes and during traditional and official events such as naming ceremonies, marriage celebrations, and chieftaincy rulings. However, its recognition as a subject of study in schools has remained out of reach, despite the efforts of some passionate individuals. This has raised concerns, especially when compared to Nzema, a language closely related to Ahanta. Nzema has been taught in schools since the time of Ghana’s first president, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, who was himself an Nzema. In fact, Nzema was once considered by him as a possible official language for the country, although that vision never came to pass.

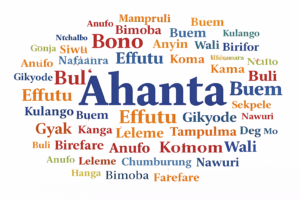

Like many other Ghanaian languages that lack formal recognition in the education system, such as Bono, Wassa, Effutu, and Sehwi, the Ahanta language has long been discussed as a potential candidate to be taught in schools. Over the years, various individuals, NGOs, and religious groups have worked tirelessly to promote the study of Ahanta in formal settings. Notably, the Ahanta Language Project has been established in the Ahanta West District to support this mission. The Jehovah’s Witnesses have developed learning materials in the language, including a manual, which shows how far the language has come and its readiness to be introduced into schools.

In addition to these efforts, there is already a hardcopy Bible available in the Ahanta language. Beyond that, a full mobile Bible application in Ahanta is also accessible on the Google Play Store for Android users. Individuals and language advocates, including Mr. Dadzie, Benyia Kofi Kyei, Joy News’ Kojo Brace, and Justice Baidoo have worked tirelessly to bring the language into the media space as part of efforts to support its inclusion in schools.

The work of Mr. Dadzie and Benyia Kofi Kyei include creating YouTube channels and online lessons where they teach Ahanta to a wider audience. There is also a dedicated radio station called Radio Ahanta, based in the Western Region, which plays a vital role in promoting the language and strongly backs Honourable Mavis Kuukua Bissue’s vision of making the study of Ahanta in schools a reality.

From a research perspective, the Ahanta language has received very limited academic attention and remains a largely unexplored area in linguistic studies. Despite this, the few existing works provide valuable insights and strongly support the idea that the language is ready to be studied in schools. One key figure in Ahanta linguistic research is Samuel K. Ntumy, himself an Ahanta native and linguist, who has dedicated significant efforts to studying the language. His research covers both phonology and aspects of Ahanta culture. Some of his notable works include Collected Field Reports on the Phonology of Ahanta [Ntumy, S. K. (2002), Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana], The Vowels in Ahanta (a Southern Bia Language) [Ntumy, S. K. (1997), Ghana Institute of Linguistics, Literacy and Bible Translation], and The Phonology of Ahanta (2002). His work also touches on cultural practices, such as his contribution to Aziziele: A Puberty Rite for Ahanta Women.

In addition to Ntumy’s work, other scholars have made meaningful contributions to the study of Ahanta. Patience Obeng, for instance, authored a paper titled Some Phonological Processes in Ahanta, which adds to the growing body of linguistic knowledge on the language. Furthermore, other researchers have included Ahanta in their co-authored studies, helping to slowly expand the academic reach of the language. While research remains scarce, these works lay a strong foundation for future linguistic studies and further strengthen the case for Ahanta to be introduced as a subject in schools.

To further support the introduction of Ahanta as a subject in schools, there are already individuals who have been informally trained and are actively teaching the language. The Ahanta Language Project has made significant strides by engaging local tutors who currently teach the language in towns like Agona Nkwanta and Busua, both located in the Western Region. Though these teachers may not have formal training in language education, their hands-on experience and familiarity with the language give them a strong foundation that can be built upon in future teacher training programs.

In addition to these tutors, there are also Ahanta individuals who are academics and professionals in various fields, including education. These individuals can play a vital role in the initial stages of teaching and training Ahanta language educators. Their involvement would not only bring credibility to the effort but also help in creating a structured and sustainable path toward fully integrating the language into the formal education system.

The Ahanta class organized by Jehovah’s Witnesses can also serve as a valuable resource in advancing the teaching of the language. This religious group has already developed comprehensive manuals in Ahanta, covering both the Old and New Testaments, which they use to teach members of the church. They also have a whole section of their site where everything on the site is in Ahanta. This shows the extent at which the language has developed in grammar, literature and culture. Their experience in using the language for structured teaching and their familiarity with written Ahanta can be a great asset in efforts to introduce the language into schools. These individuals can contribute meaningfully to curriculum development and serve as support in the initial stages of language instruction.

The presence of institutions dedicated to Ghanaian languages, such as the Bureau of Ghana Languages and the College of Ghanaian Languages Education at the University of Education, Winneba (UEW), further strengthens the case for Ahanta to be studied in schools. The College, in particular, has shown its commitment to language development by recently introducing two Gur languages, Likpakpaanl and Sissali, into its curriculum in 2022. These languages also faced challenges like the absence of trained teachers, and yet, through the support of close dialect speakers and language education experts, they were successfully integrated into the system. Currently, there are Level 400 students undergoing internships who are expected to graduate in 2025 and contribute to teaching these languages.

This track record shows that the same can be done for Ahanta. With the right support, the language can be fully incorporated into the educational system. It is no surprise that Honourable Mavis Kuukua Bissue reached out to Professor Rebecca Atchoi Akpanglo-Nartey, the Principal of the College of Languages Education at UEW, to lead the charge in making the study of Ahanta a reality. Their collaboration signals a strong and hopeful beginning for Ahanta’s future in Ghana’s classrooms.

Honourable Mavis Kuukua Bissue’s recent collaboration with the University of Education, Winneba, particularly with the Department of Linguistics and the College of Ghanaian Languages Education, marks a turning point. With plans underway to develop a curriculum, train teachers, and push for the necessary educational policies, the dream of institutionalizing the Ahanta language is gaining real traction that deserves support from all.

Editor: Ama Gyesiwaa Quansah

Hon. Mavis Kuukua Bissue’s initiative to introduce the Ahanta language into schools is commendable and long overdue. It’s inspiring to see a leader actively working to preserve and promote indigenous languages, especially one as culturally significant as Ahanta. The collaboration with the University of Education, Winneba, is a strategic move that could ensure the sustainability of this effort. However, I wonder how the community, especially the youth, will respond to this initiative—will they embrace it as part of their identity or see it as an additional academic burden? It’s also worth considering how this will impact the broader linguistic landscape of Ghana, where some languages dominate others. What steps are being taken to ensure that the teaching of Ahanta doesn’t face the same challenges as other minority languages? Lastly, how can we, as citizens, support this initiative to ensure its success? This is a step in the right direction, but its implementation will be key.