The classification of Ghanaian languages has long been a subject of linguistic debate, particularly when it comes to the Ahanta and Nzema dialects. Traditionally grouped under the Central Tano branch of the Kwa language family, these languages share similarities with both Akan and Guang, raising questions about their true linguistic affiliation. While some scholars argue that Ahanta and Nzema are closely related to Akan due to lexical similarities and cultural ties, others suggest that they may have distinct historical and structural characteristics that set them apart. This article explores the linguistic, historical, and cultural evidence to determine where Ahanta and Nzema truly belong in Ghana’s linguistic landscape.

Ahanta, also known as “Aɣɩnda”, is a dialect of the Akan language family, which is spoken by people in Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, and other West African countries (Gordon, Jr., 2005). Ahanta is primarily spoken in the Western Region of Ghana, along the coast between the cities of Axim and Sekondi-Takoradi and it is considered by Obeng (2021) as having relatively minority indegenes and minority users. According to the Ghana Statistical Services (2021) report on the 2021 Population and Housing Census (PHC), the population of the Ahantas, taking into consideration the major districts of Ahanta West, Effia-Kwesimintsim, SekondiTakoradi and Shama Districts, is 689, 721.

Previous studies by Stewart (1966) states that Ahantas are Akan people who speak the Anyi-Buale-Chakosi Akan language. The territory of Ahanta, which is now part of the Western Region of the Republic of Ghana, extends from Beposo to Ankobra. Ahanta was a confederacy of chiefdoms that held significant power in the region and had established early relationships with European nations who came to trade on the Gold Coast (Van Dantzig, 1999).

A study on some phonological process of the Ahanta language by Obeng (2021) reveals that the Ahanta language comprises of three distinct varieties. The first one is called ‘Urban’ Ahanta, spoken in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis and its surrounding areas, where the language is significantly influenced by the Fante language. The second variety is referred to as ‘Rural’ Ahanta, spoken in places like Adwoa, Funko, Ewusie Joe, Aboade, Agona Nkwanta, Busua, and Otopo. It is considered the most authentic form of Ahanta by the Ahanta people. The third variety is called Evaloe or Valoe, spoken in Princess Town, Akatekyi, Cape Three Points, and other Nzema communities beyond the Ankobra River. Evaloe is highly influenced by Nzema and is considered a variant of the Nzema language in recent times. Despite differences in sound, tone, and vocabulary, the three varieties are mutually intelligible (Obeng, 2021).

On the other hand, Nzema is a stable language spoken in Ghana and in the Ivory Coast. The language is a Kwa language and it belongs to the Niger-Congo language family (Ethnologue, 2024 Ed.). In Ghana, It is spoken in the Western Region. It is estimated that native Nzema speakers are 430, 000. In the Ivory Coast, it is spoken in the Western part (Kwesi, 1992). Just like Ahanta, as to whether the Nzema language is linguistically an Akan dialect or not has been a debate for decades.

Stewart (1966) argues that Nzema, alongside Ahanta, Anyi, Chakosi, Baule, etc. belong to the Anyi-Buale-Chakosi language. With this, Stewart (ibid.) asserts that Nzemas are only anthropological/ geographical Akans but not Linguistic Akans as some scholars argue. Amidst all the debates, Berry (1955) boldly classifies Nzema as a Bia language but goes on to say it is also one of the many Akan languages with a considerable influence from mainstream Akan languages like Fante and Asante Twi. This affirms the confusion in the existing literature on the exact classification of the languages under the so called Buale-Chakosi language by Stewart (ibid.)

In terms of mutual intelligibility, Nzema is partially intelligible to Jwira-Pepesa and it is very closely related to Ahanta and Baoulé (Bermeister, 1976). It is this same reason Stewart (ibid.) boldly classifies Nzema under Anyi-Baoulé-Chakosi language than mainstream Akan. Nyame and Ebule (2022) identify five dialects of the Nzema language: Dwɔmɔlɔ, Ɛlɛmgbɛlɛ, Adwɔmɔlɔ, Egila, and Ɛvaloɛ. Additionally, Obeng (2021) acknowledges Ɛvaloɛ, a dialect of Ahanta, as being highly influenced by Nzema and considers it a dialect of Nzema as well in her research on some phonological processes of Ahanta.

A look at the background of these two dialects shows the uncertainty in their classification, as to whether they belong to the Akan or the Guang language. But first, let us look at the criteria for classifying a dialect under a particular language.

Linguists use several criteria to determine whether a dialect belongs to a particular language group, with lexical similarity being one of the key factors. This refers to the extent to which words in one dialect resemble those in another language group. A high percentage of shared vocabulary with either Akan or Guang could suggest a closer linguistic relationship. While studies indicate that Ahanta and Nzema share a significant number of words with Akan, there are also notable differences. Moreover, many of these similarities may result from geographic proximity, as the close contact between Ahanta-Nzema and Akan-speaking communities has likely facilitated lexical borrowing.

Furthermore, Gonja and Effutu, which are recognized as typical Guang dialects, share a similar counting system, tonal patterns, phonological features, and morphological structures with Ahanta and Nzema. These linguistic similarities distinguish them from the principal Akan dialects, suggesting a closer affiliation between Ahanta, Nzema, and the Guang language group rather than Akan.

During my undergraduate studies at the University of Education, Winneba, I overheard some Gonja speakers conversing when the need for numbering arose. As an Ahanta myself, I noticed that some of their number names closely resembled those of Ahanta. Intrigued, I approached them and asked them to count from one to ten, and to my surprise, the numbers were almost identical to those in Ahanta and Nzema but different from the principal Akan dialects. This striking resemblance further supports the argument that Ahanta and Nzema may have deeper linguistic ties to at least, the Guang language group than Akan.

Another crucial factor in language classification is morphosyntactic structure, which encompasses both morphology (the formation of words) and syntax (the arrangement of words in sentences). The similarities in noun class systems, verb conjugations, and sentence construction between Nzema, Ahanta, and the various Akan dialects provide strong support for scholars who argue that Ahanta and Nzema belong to the Akan language group.

| Sentence | Language | Subject | Verb | Object | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwame lɛkɔ sukuulu | Nzema | Kwame | lɛkɔ (progressive) | sukuulu | Kwame is going to school |

| Kwame rokɔ skuul | Akan | Kwame | rokɔ (progressive) | skuul | Kwame is going to school |

| Kwamɩ yɩ kɔ sukuulu | Ahanta | Kwame | yɩ kɔ (progressive) | sukuulu | Kwame is going to school |

Syntactically, both Ahanta and Nzema follow the Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) sentence structure, just like the Akan dialects. In this structure, sentences begin with the subject, followed by the verb, and then the object. However, considering the data in the table above, this criterion alone does not provide a strong basis for classification, as all Kwa languages adhere to the same sentence structure. This makes the argument inconclusive from a syntactic perspective as well. Where do we go again?

| English | Ahanta | Nzema | Akan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Kizile | Kinzile | Dwowda/Dwoada |

| Tuesday | Twɔkɔ | Dzɔkɛ | Benada |

| Wednesday | Manlɩ | Maalɩ | Wukuda/Wukuada |

| Thursday | Kulo | Kule | Yawda/Yawoada |

| Friday | Yaalɛ | Yaalɛ | Fida/Fiada |

| Saturday | Fʋlɔ | Folɛ | Memenda |

| Sunday | Bɔɔlɔ | Mulɛ | Kwesida/Kwesiada |

Although the Akans, including the so-called Akans in Ahanta and Nzema, as well as the principal Akan groups, use day names in personal naming, it is interesting to note that the day names in Ahanta and Nzema are more similar to each other than to those in Akan. This distinction is evident in the table above.

Furthermore, Dolphine (1975), in her work Languages of the Akan People, made an observation that is worth considering. She noted that Ahanta and Nzema begin their week with Monday, whereas the Akan people start with Sunday. Interestingly, this same pattern is found in Gonja, a language long recognized as part of the Guang language family. This striking similarity further reinforces the argument that Ahanta and Nzema may have stronger linguistic ties to the Guang group rather than Akan. Well, the argument is failing in favor of Akan anthropologically as well.

Mutual intelligibility is another crucial criterion that cannot be overlooked when classifying languages. It refers to the degree of understanding between two languages or dialects. The data presented in the table above serves as evidence of the differences between Ahanta and Nzema on one hand and the principal Akan dialects on the other. If you are a speaker of at least Ahanta or Nzema and Akan, as I am, you would recognize that the gap in comprehension is too wide to consider them as part of the same linguistic group.

Ahanta and Nzema speakers understand Akan primarily due to the widespread exposure of the Akan language across Ghana and the geographical proximity of these language groups. However, Ahanta and Nzema are more mutually intelligible with Sehwi, Anyi, Baule, and what Dolphyne (1975) classified as the Nzema-Anyi-Baule language group. This raises an important question: while Ahanta and Nzema speakers can understand Akan, how many Akan speakers can comprehend Ahanta and Nzema when spoken? This lack of two-way intelligibility weakens the argument that Ahanta and Nzema belong to the Akan language group, as they fail the fundamental criterion of mutual intelligibility.

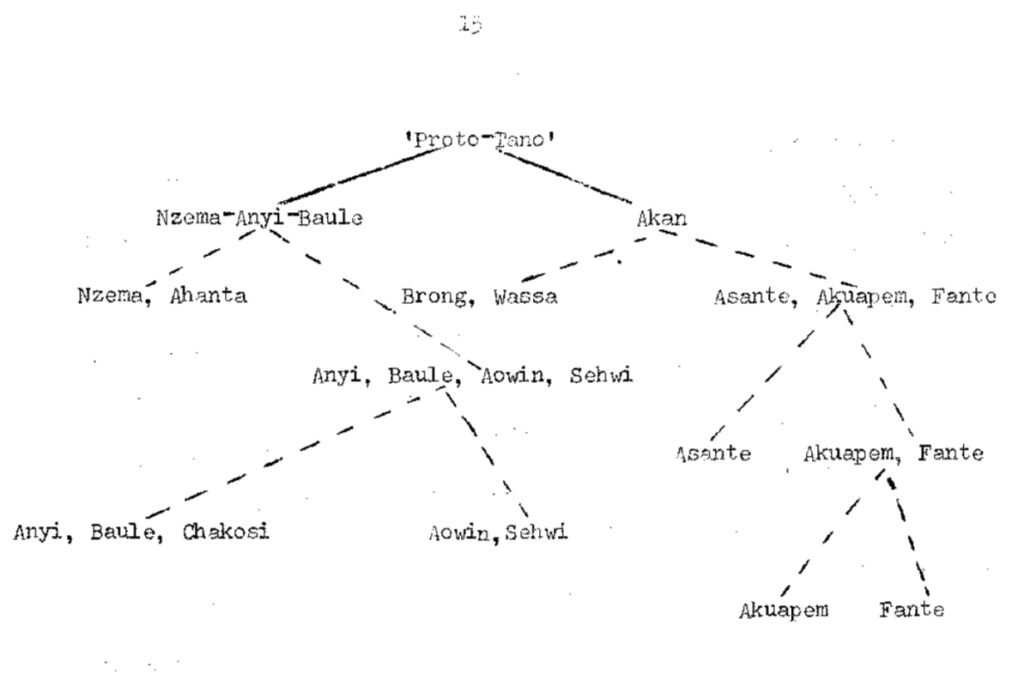

two languages in terms of the stages through which they broke away from

each other- The straight lines link langu-ges and the broken lines

link dialects. Source: Dolphyn (1975).

In conclusion, I align with the school of thought that argues Ahanta and Nzema do not belong to the Akan language group but rather to another linguistic classification, possibly the Guang group, Bia group or what Dolphyne (1975) identifies as the Nzema-Anyi-Baule group. The linguistic evidence, including phonological similarities, shared counting systems, and distinct day names, suggests a stronger connection between Ahanta, Nzema, and other non-Akan languages.

Moreover, the issue of mutual intelligibility further challenges their classification as Akan. While Ahanta and Nzema speakers may understand Akan due to geographic proximity and language exposure, Akan speakers struggle to comprehend Ahanta and Nzema. This one-sided intelligibility weakens the argument that these languages belong to the Akan group. Instead, their linguistic features and intelligibility patterns align more closely with languages traditionally considered outside the Akan classification. Thus, it is time to reconsider their linguistic affiliation based on solid linguistic criteria rather than historical, anthropological or sociopolitical assumptions.

Editor: Ama Gesiwaa Quansah

I am really impressed together with your writing abilities

as smartly as with the format for your blog. Is this a paid theme

or did you modify it your self? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it’s

uncommon to see a great weblog like this one these days.

Stan Store alternatives!

Thank you for your words. It’s not a paid theme. It’s a modified one. Thank you for loving it.

kyer3kyer3nyi please do you have an article on fante people, the seperations, and where they can be found in ghana.

I will work on that for you Sir. Thank you for enjoying our contents.

You are in Ghana and you don’t know the geographical location of fantes like seriously